A few useful things to know about Machine Learning

An overview of the paper “A few useful things to know about Machine Learning”. The author creates a brief introduction of the important concepts that guide machine learning. All images and tables in this post are from their paper.

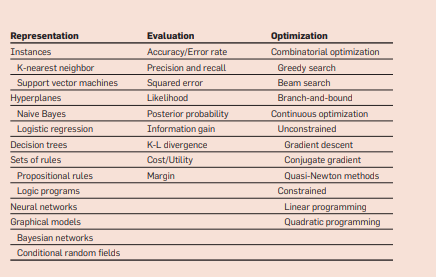

Learning = Representation + Evaluation + Optimization

Regardless of how many new models are out there, all models can be fundamentally broken down into these three simple components. Representation refers to the sequence of symbols which the computer can understand. Evaluation refers to the objective function that seperates the good classifier from the bad one. Finally, optimization refers to the method which allows the learning of the model.

The three components of learning algorithms.

It’s Generalization that Counts

The fundamental goal of a model is to generalize beyond the examples in the training set. Contamination of your classifier by your dataset can come in insidious ways. If one chooses to tune the hyperparameters, based on its performance on the test set, we do reach the aforementioned scenario. Unlike in most other optimization problems, we do not have access to the function we want to optimize! We have to use training error as a surrogate for test error, and this is fraught with danger.

Data Alone Is Not Enough

Machine Learning is an inductive process. It learns the representations with many examples. However, you would need prior knowledge to create a good model. Luckily, the functions we want to learn are not drawn randomly from all possible mathematical functions. In fact, very few assumptions such as similar examples have similar classes, smoothness, etc. are good enough in most cases. However, one must choose the right model whose assumptions are in coherence with the data.

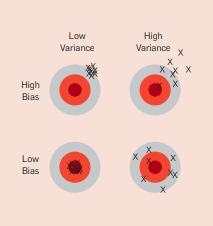

Overfitting Has Many Faces

When the knowledge and the data is not sufficient to train a complete model, the model might hallucinate traits and might not generalize properly. This leads to overfitting. The generalization error can be decomposed into bias and variance. Bias is the learner’s tendency to consistently learn the wrong thing. Variance is the tendency to learn random things irrespective of real signal. Few solutions to overfitting include cross validation, regularization, dropout, etc.

Bias and Variance.

Intuition Fails in High Dimensions

The biggest problem in machine learning is the curse of dimensionality.Generalizing correctly becomes exponentially harder as the dimensionality (number of features) of the examples grows, because a fixed-size training set covers a dwindling fraction of the input space. In high dimensions, most of the mass of a multivariate Gaussian distribution is not near the mean, but in an increasingly distant “shell” around it. Naively, one might think that gathering more features never hurts, since at worst they provide no new information about the class. But in fact their benefits may be outweighed by the curse of dimensionality.

Theoretical Guarantees Are Not What They Seem

The most common type is a bound on the number of examples needed to ensure good generalization. In deduction you can guarantee that the conclusions are correct; in induction all bets are off. Such guaranteees have to be taken with a grain of salt. It only says that, if the hypothesis space contains the true classifier, then the probability that the learner outputs a bad classifier decreases with training set size. Furthermore, asymptotic guarantees which claim that given infinite data, the learner will give the correct classifier is not entirely useful. Due to the bias-variance tradeoff, an asymptotically guaranteed model might perform once that another model given finite data.

Feature Engineering Is The Key

Feature engineering is domain specific and is easily one of the most important factors of the performance of your model. One automated way is to generate a candidate features and selecting the one with the highest information gain. A feature, which is in isolation might not be useful. However, a feature transformation such as XOR, etc. can ultimately save you both time and avoid overfitting.

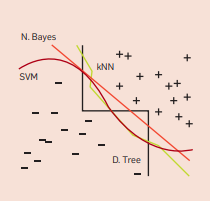

More Data Beats a Cleverer Algorithm

A dumb algorithm with lots of data beats a clever one with modest amounts. Hence, we might work with a more simple algorithm than a complex time consuming algorithm. Most models work in a similar fashion, they work by grouping nearby examples into the same class. The key difference is their understanding of nearby. As a rule, it would be preferred to try out the simple algorithms before moving on to the more complex ones. Learners can further be divided into non-parametric/variable size and parametric/fixed size learners. Variable size learners can in principle learn any function given sufficient data, but in practice they may not, because of limitations of the algorithm such as falling in a local minima or computational costs. With nonuniformly distributed data, learners can produce widely different frontiers while still making the same predictions in the regions that matter.

Very different frontiers can yield similar predictions.

Simplicity Does Not Imply Accuracy

Given two classifiers with the same training error, the simpler of the two will likely have the lowest test error. However, this need not always hold true. Thus, contrary to intuition, there is no necessary connection between number of parameters of a model and its tendency to overfit. A learner with a larger hypothesis space that tries fewer hypotheses from it is less likely to overfit than one that tries more hypotheses from a smaller space.

Representable Does Not Imply Learnable

The author raises the point, if the hypothesis space has many local optima of the evaluation function, as is often the case, the learner may not find the true function even if it is representable. Given finite data, time and memory, standard learners can learn only a tiny subset of all possible functions, and these subsets are different for learners with different representations.

Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

This is a very obvious statement. Even if a said feature seems to cause a change in the target variable, it might be completely irrelevant to the experiment. Unfortunately, our data is such that the said feature could be used to predict a target variable even when there is no causation behind it.